In a very influential article, Mayer and Lopoo (2008) find that government expenditure increases intergenerational mobility (IGM). This implies that public spending mediates parental income and reduces the incidence of becoming poor in the long-run. However, these type of state interventions are highly heterogenous across poor and rich cohorts in low or high-spending regions. In addition, three issues are worth stressing. First, public spending programs are not well-target towards distressed places (e.g., the “ARRA”). As a result, the welfare effects of “broad” (health, justice, education, transportation and facilities) or “core” (highways and bridges, air transportation, sewage systems) investments are slack (5 to 10 years). Therefore, parental investment decisions among rich families could be crowd-out by government actions (Solon, 2004). Second, parental measures of income are subject to mismeasurement if households do not report their true source of income or else if adults face intergenerational financial borrowing constraints (Mulligan, 1999; Han and Mulligan, 2001). Instead, the level of education, once acquired, does not vary across the lifecycle. Third, a higher supply of infrastructure services like ICT (main line telephones, cell-phone mobiles and broadband internet) could positively influence children’s “neural” development. Indeed, at early stages the timming and initial conditions will ultimately define their outer limits (e.g., stress, mental well-being, behavioral problems, etc) or else their success in labour markets, socioeconomic status and family formation like parenting (Corak, 2016).

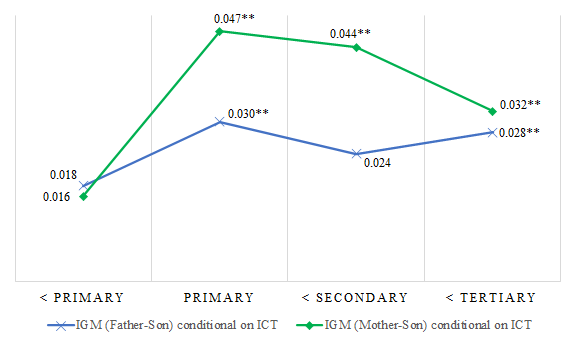

Usually, the literature focuses on the father-son relationship. Instead, I provide a decomposition of the IGM in education conditional on ICT use for both parents. To this end, I combine a micro panel data of 5 different cohorts (1940, 1950, 1960, 1970 and 1980) with macro data in both developed and developing countries up to the latest available year. I present only the indirect effect of all children, i.e. ICT mean schooling years children’s → IGM (absolute) in adults. The direct effect i.e. schooling returns → IGM (not reported) is positive and statistically significant across cohorts and education levels. Naturally, the total effect is composed by the sum of both direct and indirect effects. Given that endogeneity is likely to occur, I employ 2SLS using historical deep lags of economic development from multiple periods as instruments. As Figure 1 shows, there is distinctive sharp gap between father-son and mother-son IGM in education conditional on the use of ICT. The mother-son link (all children) with at least primary education completed is higher with respect to males. For higher education levels, the female line is above its counterpart (male) and continues to be significant. First-stage statistics (available upon request) are well-above the threshold value of 10 (Staiger & Stock, 1997) which support the casual relation for each level of education. In regards to ICT contribution, if the mother (father) did not complete primary school, ICT explains roughly 21% (23%) of children’s future mobility; 53% (37%) for completed primary; 68% (40%) for incomplete secondary and finally 47% (41%) for incomplete tertiary/university respectively. This simple exercise confirms that ICT infrastructure has a positive effect at early stages of childhood, primary and secondary school and that children are more likely to acquire e-learning skills and higher schooling returns through internet services and smartphones. In terms of policymaking implications, results do not necessarily imply that two countries should spend the same fraction of their GDP on infrastructure nor transfer more ICT resources to children as it neglects the very true nature of the issue i.e. the quality-quantity trade-off of parental investment decisions in regards to children’s education.

Figure 1: Infrastructure and IGM in Education